Epidemiologist and former Captain of the USPHS/Vessel Sanitation Program, Mr. George Vaughan, provides information on how to anticipate and mitigate potential consequences of acute gastroenteritis outbreaks onboard cruise ships

Epidemiologist and former Captain of the USPHS/Vessel Sanitation Program, Mr. George Vaughan, provides information on how to anticipate and mitigate potential consequences of acute gastroenteritis outbreaks onboard cruise ships

“There are a few ways in which outbreaks are characterized or defined. First, the U.S.P.H./Vessel Sanitation Program (VSP) defines an outbreak based on a set of symptoms experienced by a group of cases. A case is currently defined as, diarrhea (three or more episodes of loose stool in 24 hours or what is above normal for the individual) or vomiting and one additional symptom including one or more episodes loose stools in 24 hours, or abdominal cramps, or headache, or muscle aches, or fever (defined as 100.4°F or 38°C) or feeling “feverish.” It is important to note that case counts include only those persons who report their symptoms to the medical representative aboard the vessel. An outbreak of acute gastroenteritis - AGE - is established when the number of reported cases meeting the case definition is equal to or exceeds three percent in either passenger or crew members in any single voyage or voyage segment in the event of a long voyage.

Second, laboratory confirmation of an outbreak may also be established by a standard set of symptoms and laboratory confirmation of a pathogen such as salmonella in clinical specimens. It is typically based on two or more cases meeting the case definition associated with the ship in place and time. The AGE cases do not necessarily have to occur in a single voyage. These cases usually come to the attention of the VSP through laboratory reports from local and state health departments.

Finally, an outbreak may occur in a cluster of cases based on the syndromic definition that does not reach the three percent threshold. Case clusters may be identified in a subset of the population with an exposure limited to a few people, exposed to contaminated food in a single restaurant. The three percent threshold is not reached simply because the primary exposure is limited to a small number of people.

In any of the scenarios described, an outbreak is established and could result in an onboard investigation by public health authorities.”

An important note for the medical staff - there are severe penalties for underreporting AGE cases.

“Outbreaks of acute gastroenteritis can result from ingestion of contaminated food or water, person-to-person spread and contact with contaminated surfaces in the environment may occur. The contamination may be due to a microorganism such as bacteria, viruses, and parasites, or less likely, from chemical or physical agents. In the case of outbreaks caused by microbial agents, secondary AGE cases may occur from the person-to-person spread or environmental contamination. Contamination events may occur on or off the ship.

Regardless of the cause, the outbreak must be controlled as quickly as possible to minimize the number of people affected.”

“That depends on the circumstances surrounding the outbreak. While ideally all outbreaks should be investigated on board the vessel, it is not practical to do so. Consideration is given to the following set of variables to determine whether an outbreak investigation will be conducted onboard a vessel:

There may be others specific to the characteristics of the outbreak event.”

“Before the occurrence of an outbreak, it is critical to establish strategies for intervention. Since the publication of the 2005 version of the Operations Manual, the VSP requires that all ships have a written Outbreak Prevention and Response Plan (OPRP). The main objective of the plan is to establish coordinated response procedures to minimize morbidity (illness) and possible mortality (death) in both passengers and crew populations. These plans describe the response actions to be taken by each department during a shipboard outbreak of acute gastroenteritis. The plan establishes when the response actions occur based on trigger points for phased-in response activities and must increase response action in the face of increasing cases.

So, the primary objectives of the OPRP are to ensure that the ship’s staff is prepared to respond swiftly and effectively when an outbreak is imminent and to plan, in advance, for the resources necessary to stop the progression of the outbreak."

"Certainly. The VSP requires that all OPRPs contain some essential elements to be considered comprehensive. The details of the OPRP should reflect the size and complexity of the operations of the vessel and should incorporate the outbreak response considerations for the specific platform. It is recognized that OPRPs may differ from ship-to-ship or for a particular class of ships. At the very least, the following elements must be included in the plan:

An OPRP can have additional sections that are specific to a cruise ship or cruise line.

“I believe that outbreak communications (a form of crisis communication) are an important component of outbreak management. Keep in mind that passengers who board the vessel expect to have a safe,healthful, and enjoyable vacation. During an outbreak, that “once-in-a-lifetime” experience has been compromised, even for passengers who are not cases since cruise activities are sometimes suspended or canceled.

Appropriate and sensitive communications regarding the outbreak are essential in minimizing the impact on brand reputation, adverse publicity, as well as adverse legal repercussions. A few communications tips for passenger and crew members aboard an outbreak voyage to keep in mind are as follows:

When you communicate openly and honestly with those affected, the tendency is that they, for the most part, will be less hostile, and in some cases, support you in your efforts.

With proper outbreak communications, you can take control of a challenging situation and gain the confidence of your stakeholders.

In addition to stakeholder considerations, there are legal and regulatory reporting requirements that must be adhered to also. Case reporting, daily update reports, and required telephone notifications must all be done appropriately through established procedures. Prompt communication is needed so that the appropriate public health authorities can monitor the outbreak and take action as required. The lack of proper outbreak communications can result in severe consequences, such as preventing your ship from sailing on the next voyage.”

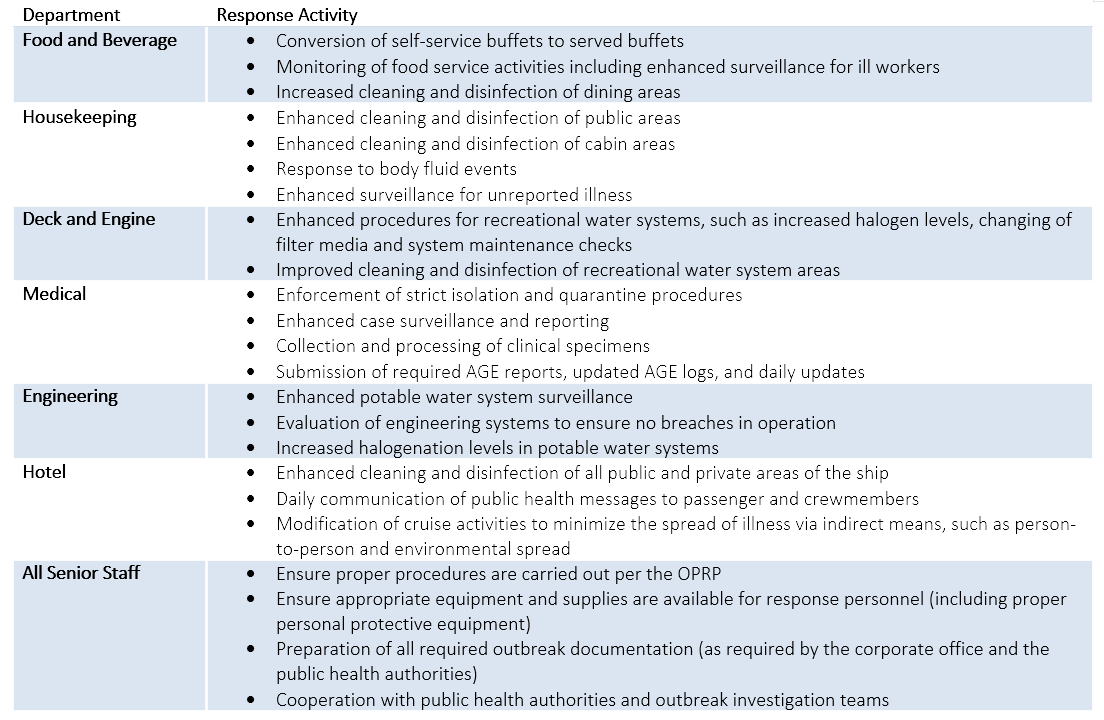

“First of all, it goes without saying that outbreak response is an “all-hands” event. Each department will play a significant role in its resolution. I have included a table which summarizes some of the more important activities that may be required by specific departments:”

“These activities and others must be carried out successfully while providing for the daily operation of the ship. Therefore, it's clear that the way to accomplish this is through a coordinated response.”

“I will begin by saying that, it is essential that the staff understand that while they are out at sea, they are the person who will evaluate the early stages of an outbreak. This concept is particularly crucial during voyages where there are long stretches of days at sea, since the opportunity to supplement the ship’s staff with outside expertise is not possible. In this case, the available team must utilize their resources. Some activities that I recommend the ship’s crew undertake to include the following:

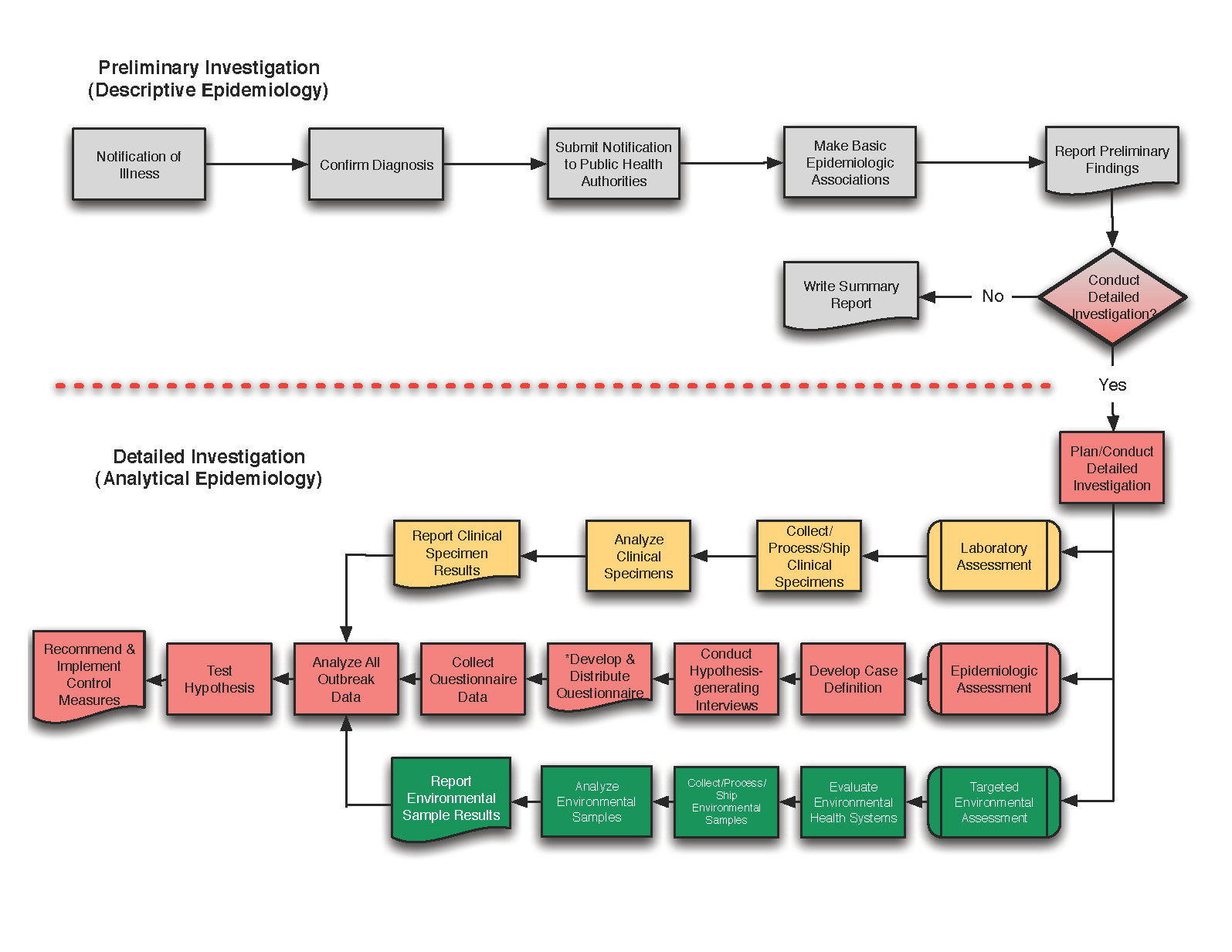

“Certainly. First, let me point out that this flowchart was designed to be a broad overview of the necessary steps in an outbreak investigation. An outbreak investigation typically involves many more steps and activities than are outlined here. This flow chart intends to provide appropriate direction to the ship’s staff as to the activities they make undertake when faced with a significant elevation of cases or when they are in the midst of an outbreak.

The flow chart is divided into two major sections corresponding to staff capabilities(indicated by the gray-colored components above the dashed line) and that which will require outside expertise and resources (shown by the yellow, pink, and green flow chart components below the dashed line). This division roughly corresponds with what could be described as the descriptive (epidemiology) component and the analytical (epidemiology) component. The descriptive element seeks to understand the “who,” “what,” “when,” “where” of the outbreak. The analytical component aims to get at the “why” and “how” of the outbreak. The decision diamond in the upper right part of the diagram is shaded gray and pink to indicate the joint decision of ship, corporate staff, and public health authorities to conduct an onboard investigation (or conversely, to conclude the inquiry). This decision is based on several factors, some of which were discussed in a previous Q&A above. The primary focus of the ship’s activities is to identify (if possible) any deviations from normal operations and public health practices that might have contributed to the cause or the continuation of the outbreak.

At the beginning of an outbreak (or elevated cases), the ship may be at sea or outside public health jurisdiction. So the initial investigation activities will fall upon the ship’s leadership. Usually, an outbreak is first identified by an unexpected and sometimes sudden rise in cases observed by the medical staff. The medical staff informs the senior leadership of the vessel (and the corporate office) of the observed increase in AGE cases. It may result in the activation of the OPRP if the pre-defined trigger levels have been reached. At this point, the medical staff should thoroughly evaluate the diagnosis of cases to confirm whether an actual elevation has occurred and not associated with say, seasickness. For most AGE outbreaks, this is not an issue. However, on ships with small passenger and crew populations, this might not be the case, since a small number of cases result in reaching the notification and outbreak thresholds. Once the diagnosis is confirmed and the elevated cases verified, the ship is required to notify public health authorities. In the case of the VSP, a Special Report is needed whenever the vessel has ≥ 2 percent reportable cases of AGE in either passenger or crew populations and is within 15 days of arrival at a U.S. port. The Special Report is submitted through the electronic Maritime Illness and Death Reporting System (also known as MIDRS), and a telephone notification (or email) to the VSP is required at the time the Special Report is submitted. At the 2 percent threshold, the VSP staff will request the ship to provide daily or twice-daily updates. These reports allow VSP to monitor the progression of the outbreak, review outbreak-related data, prepare for a possible onboard investigation, and make recommendations for control. The 2018 VSP Operations Manual requires the ship to submit a second Special Report when case counts are ≥3% in either passenger or crew populations.

Once a pending or actual outbreak is established, the ship’s senior staff must begin the search for clues to the initiation of the outbreak. Each department should start the investigation process by looking for unusual occurrences or events up to 2-3 days before observing the initial rise in cases. The reviews should be done with an open mind and with the intent of identifying facts that might shed light on the cause of the outbreak.

Since one of the most common activities on board the ship involves food and beverage (including water and ice) consumption, the F&B Department staff should concentrate on events surrounding food and beverage procurement, preparation,storage, and service. The F&B staff should review all documents associated with the food service operations including time and temperature logs, cooling logs, maintenance records of galley equipment.

The F&B senior staff should conduct enhanced case surveillance through personal interviews with the F&B staff to determine if any staff member worked (for any length of time) with diarrhea or vomiting symptoms, even if the symptoms appeared to be mild. If a food employee is identified as symptomatic, immediately remove the food employee from food operations and have him/her report promptly to the medical infirmary. The work area must be surveyed for contamination by the food employee and removed immediately. The area should be thoroughly washed, rinsed,and sanitized per the ship’s OPRP.

The medical staff should obtain a stool or vomit specimen from ill food employee(s) for subsequent analysis at a designated laboratory. It is strongly recommended to collect a stool specimen, even if the person no longer is symptomatic with diarrhea.

If during the evaluation, a food or beverage item is believed to be the vehicle in the outbreak, samples of the food or beverage should be collected, prepared, and retained for subsequent laboratory analysis. Consult with the public health agency with jurisdiction or laboratory for procedures and documentation requirements for processing the samples.

The medical staff should conduct a thorough review of all medical records of cases that reported with symptoms of diarrhea and vomiting, even if they were considered mild and not reportable. The survey should include the medical log, the AGE surveillance log, and the 72-hour standard questionnaires for the outbreak cruise/cruise segment, as well as the previous cruise or cruise segment. The medical staff should keep in mind that the beginning of an outbreak may have been initiated by illness in the last voyage, especially among crew members. The number of AGE cases does not have to reach the notification level to be considered significant. The medical staff should construct an epidemic curve of the number of AGE cases by date and time of illness onset (not by date of reporting to the medical infirmary). This graph can be very instructional as to the type of outbreak as well as suspected mode(s) of transmission and possible vehicles. In addition to the epidemic curve, the medical staff should calculate frequencies of cases by age, gender, passenger or crew status, symptom type, crew position, cabin location, and dining room seating/meal period. These data may give clues as to the cause of the outbreak and help to generate hypotheses for further evaluation.

The medical department staff should collect and process all clinical specimens obtained in support of the outbreak investigation. This process may require contacting the first cases and requesting a stool or vomitus specimen. Depending upon the suspected pathogen type, the clinical specimen may require collection in a stool specimen collection container or on a bacterial transport medium, such as Cary-Blair or ParaPak C&S.

The Engineering Department staff should review all maintenance records, logs, and documents for any unusual occurrences or deviations from standard procedures in potable water bunkering, production, and distribution systems as well as any significant cross-connection control issues for the preceding month, including the period of the outbreak. The staff should review all microbiological analyses conducted for the same period. Also included in the evaluation should be any work done in the food areas, including cleaning and maintenance of ice machines. The Deck and Engineering Department should conduct a thorough assessment of the recreational water facilities (RWFs) for the same period. Particular attention should be paid to the halogenation and pH requirements, maintenance, and operations records, including water changes (where applicable), filter and filter housing servicing, and backwashing as required in the VSP Operations Manual.

Finally,I recommend that the Housekeeping Department staff report all episodes of public diarrhea and vomiting events, including those that preceded the initial spike in cases. All responses to body fluid events should be documented in a log and include the name of the person (if known), location of the release, type of body fluid release, name of responders, and a summary of cleaning and disinfection procedures. Also, observations of unreported illness among passengers (or crew) should be reported to the medical staff promptly so they can be adequately evaluated and medically monitored, so the size and extent of the outbreak can be determined. Ensure that all responders to body fluid events are fully trained and protected from the contamination and the disinfectant used in the cleanup to minimize occupational exposures.

When pertinent information is gathered, it should be reported immediately to the public health agency with jurisdiction, such as VSP. After the information-gathering period, recommend a summary report be submitted to the public health agency with authority.

Based on the progression of the outbreak and collected information, there may be a decision to conduct an onboard outbreak investigation. At this point, outside expertise is usually dispatched to do the analytical portion of the study. During this phase of the investigation, the ship’s staff is responsible for supporting the outbreak investigation team by providing the assistance required to ensure the success of the study, as well as the implementation of all recommended outbreak control strategies.”

“Yes, I do have a few final thoughts. First and foremost, I need to stress that a critical component in outbreak management is avoiding an outbreak in the first place. That is the outbreak prevention component of the OPRP. The ship’s staff should avoid all high-risk practices that invite outbreaks of AGE. These high-risk activities are designated as critical items in the VSP Operations Manual and are science-based. These public health standards are established to protect the public’s health. Therefore, the ship’s staff must comply with the standards at all times if outbreaks are to be averted. Critical violations in these standards place shipboard populations at an increased risk of an outbreak. Many outbreaks are avoidable. The ship’s leaders must ensure that the staff complies with “all of the rules, all of the time.” I recognize there are differences between public health standards worldwide, but for the most part, most of the measures are designed to be protective of the public’s health. Should a particular element of a standard is deemed to fall short of this objective, then it is incumbent on the cruise corporation to set a higher standard of protection. Since noroviruses cause most of the outbreaks observed over the past several years, I have the following suggestions for areas of emphasis during normal operations:

Secondly,when an outbreak does occur, a sound strategy for outbreak management will increase the chance for a successful outcome dramatically. After an outbreak response, evaluate the entire outbreak response effort to determine, what went wrong, what was done well, and how you can improve upon it should you have to respond again. This procedure should provide the ship’s staff with an opportunity to improve upon the outbreak plan based on lessons learned. The leadership staff should openly and honestly evaluate their response posture and take the appropriate and necessary action to avert the outbreak, as well as improve upon outbreak response strategies (where warranted). The review process allows management to assess their response vulnerabilities and capabilities and to modify response actions. I also recommend that this review be finalized in writing and shared with the corporate office and sister ships.

Thirdly, don’t assume that the pathogen was “brought on board by passengers.” On the contrary, the first assumption should be that it is on the ship and possibly in a crew member. You should rule out your staff first before asserting that the illness was brought on in the passenger cohort. The only accurate way to make that assessment is through a complete outbreak investigation.

Lastly, I was advised by a Norovirus subject matter expert that enteric pathogens such as norovirus come up the gangway on just about every cruise. It is not a matter if it is there, but rather how you manage it once it is aboard ship. Your staff should be appropriately trained and equipped for outbreaks of any of the common enteric pathogens identified in cruise ship-associated outbreaks of acute gastroenteritis, not just noroviruses.”

Interview posted with permission from Capt. (ret) George H. Vaughan

P.O. Box 1257

Windermere, FL 34786-1257

United States of America

Website Design by Parasol Designs

Animation Design by Gregory Greenidge

Podcast Interviews by Maria Florio

Website Design & Development by Parasol Designs

Animation Design by Gregory Greenidge